Unit Bruises: Theodore Wan & Paul Wong, 1975-1979

Richmond Art Gallery

April 20 – June 30, 2024

Curated by Michael Dang

Artist Talk May 25, 2024, 2pm

Unit Bruises brings together the works of two Chinese-Canadian conceptual artists active during the 1970s: Theodore Saskatche Wan (b. 1953; d. 1987) and Paul Wong (b. 1954). By mobilizing their own respective bodies, and the visual languages of medical and procedural illustrations, both artists subverted notions of objectivity that have been naturalized through such hegemonic imagery. Through these intensely physical works, the two artists respectively asserted their othered subject-positions as people of colour as well as ruminated on the topics of illness, death, and the human condition.

This exhibition is presented with the support of the Audain Endowment for Curatorial Studies through the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory in collaboration with the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery at the University of British Columbia.

Unit Bruises is part of the 2024 Capture Photography Festival Selected Exhibition Program.

Works included in exhibition:

Blood Brother

(compilation ft. 60 Unit; Bruise & 50/50)

Kenneth Fletcher / Paul Wong (1976-2024)

7:45 min., stereo, colour, English, single-channel w/ credit

in ten sity

Paul Wong (1978)

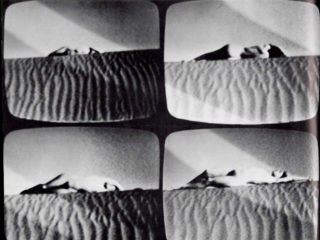

b/w, 25 min., stereo

Originally performed and recorded as a live performance Dec 7, 1978

5 channel video installation, (1978)

single channel edit (1978)

single channel mix (2008) digitally remastered

7 Day Activity

Paul Wong, (1977-2008)

8:30 min., stereo, colour, English, single-channel w/ credits

7 Day Activity Photo Panels

Paul Wong (1977)

1 of 1, Colour photography dry mounted on flesh coloured card

23.5″ x 16″

Day 1 Soapdish

Day 2 Mint Suled

Day 3 Apricot Cleanser

Day 4 Alcohol

Day 5 Zinc Ointment

Day 6 Tower Rack

Day 7 Condom Extractor

Unit Bruises Poster Essay

Theodore Sasketche Wan (b. 1953, Hong Kong – d. 1987, Vancouver, BC) and Paul Wong (b. 1954, Prince Rupert, BC), respectively two Canadian artists of Chinese descent from the same generation, both worked in and around Vancouver in the 1970s and mobilized techniques of body art and lens-based practices in the lineages of conceptualism. Unit Bruises marks the first time that Wan and Wong’s respective contemporaneous practices have been juxtaposed together in a two-person exhibition. This juxtaposition elucidates the heightened differences between the two artists’ respective backgrounds and practices, and how both responded to similar problems as two individuals of a racial and ethnic minority working in predominantly white spaces in the 1970s. Both artists appeared to be interested in body and performance art as the then-new phenomenon had the potential to radically dislodge naturalized structures and stereotypes, as art historian Amelia Jones would later write, through the assertion of “othered” subject-positions. Notably both artists subverted notions of objectivity by taking up the codified visual languages of medical and procedural illustrations, as perpetrated by such official institutions of control and surveillance as hospitals and prisons, albeit in much different fashions. All of the works in Unit Bruises are self-portraits, in some form, in which the respective artists turned the camera onto themselves and pushed their own bodies to their limits. Unit Bruises argues that Wan and Wong’s contemporaneous practices were complementary, in that both artists emphasized their visible differences as Chinese-Canadian men (and queer, in the case of Wong) by subverting the Cartesian dualisms of the subject/object as well as hegemonic notions of objectivity and universality.

Wong recalls being an acquaintance of Wan, particularly in the early 1980s when Wan’s Main Exit gallery was located mere blocks away from the video-art centre Video Inn that Wong was associated with since its inception. However, this exhibition focuses on the period when both artists were coming of age in the 1970’s, coinciding with the emergence of many artist-run centres in the Vancouver area including but not limited to Western Front, The Satellite Video Exchange Society/Video Inn (both opened in 1973), and Pumps (opened in 1975). These new alternative arts spaces allowed for creative types to have greater administrative and creative autonomy at arm’s length from more traditional arts institutions, which included more multidisciplinary experimentation and fostering of international networks of communication between artists. While Wan and Wong had varying degrees of involvement in the prominent artist-run centres of the time–with Wong being extremely active in both Western Front and Video Inn and Wan mainly being a peripheral figure in this scene–this context of international artists’ networks is important to understand both artists and their influences. A hallmark of both local and international artists involved in these networks was the creations of personas and aliases, which gave these artists recognizable personal brands, allowing them to also investigate the ways in which identity and the self was constructed through mass-media images. In addition, ritualistic and masochistic performance work throughout Europe and the United States–characterized by the Viennese Actionists, Joseph Beuys, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden, and so on–had been recognized throughout Canada with such artists visiting hub-centres, such as Wan’s alma-mater NSCAD University in Halifax and Western Front, for talks and performances. While less involved than Wong in Vancouver’s artist-run centres during the 1970s, Wan was known to be hyper-aware of these currents in both local and international art. Through Wan’s more traditional post-secondary arts training, the artist was immersed in conceptual art theory having interacted with many prominent contemporary artists during his studies for his BFA at UBC and an MFA at NSCAD. Because of this phenomenon of forward-thinking artistic centres fostering international networks, Wan and Wong were both heavily influenced by the avant-garde body and video art of their era that was predominantly made by white practitioners.

In albeit much different fashions, Wan and Wong both responded to the expectations of individuals of Chinese descent to culturally assimilate into white Canadian society. Wan responded to these hegemonic expectations through satirical mimicry, leaning into assimilative values to a comical degree. This theme of assimilation is most explicit in Name Change (1977), a conceptual work in which Wan applied for an official name change from “Theodore Fu Wan” to “Theodore Sasketche Wan,” a change that satirically signaled an immigrant fully integrated into dominant Canadian culture and “its” land. Wong responded to assimilative expectations much differently, railing against societal norms in an antagonistic punk-like fashion, identifying with the “freaks and outsiders,” that blurred the discreet spheres of art and life. From around 1972 to 1982, Wong was part of the Mainstreeters, an “art gang” made up of a close-knit group of friends who had met while attending Sir Charles Tupper Secondary School. The Mainstreeters, including Wong’s close collaborator Kenneth Fletcher (1954-1978), collaborated on numerous video works with the newly accessible Sony Portapak whilst hanging out and living together in the area near Vancouver’s Main St. Such influences from the punk scene can be seen in In Ten Sity (1978), a work dedicated to Fletcher following his death by suicide, in which the artist thrashes, dances, and moshes in a padded institutional-like cube.

While in hindsight many of these intensely physical works appear to be eerily prophetic, in regards to both Wan and Fletcher’s untimely deaths, it is important to remember the artists’ intentions at the time. Wong remembers that 60 Unit; Bruise (1976), in which Fletcher injects his blood into Wong’s back via a syringe, was conceived not as a rumination on death but as a means to test out Western Front’s new colour camera. In addition, the withdrawal and injection of blood was intended to be a school-boy-like “blood-brother” ritual that spoke to the close bond between the two men. Similarly close friends of Wan’s, such as Christos Dikeakos and Paul Hess, remember Wan’s interest in medical devices not as an obsession with death or illness, but rather as a lighthearted curiosity in the mechanics of medical equipment and its uses. What is often lost in the posthumous discussion of Wan’s work, especially in light of his death from cancer at age 33, is the artist’s dry and sardonic sense of humour (as seen in Name Change and his series of Microscopic Images of the Artist’s Sperm, both 1977). In addition, Wan’s intent with his series of medical and surgical-style instructional photographs in which he played the “patient”–including Bridine Scrub For General Surgery (1977) and Bound By Everyday Necessities I and II (both 1979)–was to incorporate notions of the Duchampian readymade into his photography which explored the functionality and reception of art objects in different contexts. Notably, the Bound By Everyday Necessities series was first exhibited simultaneously in two distinct contexts: in a traditional gallery setting, where the photographs were seen as conceptualist interventions, and also at the Victoria General Hospital, where the works were seen as instructional documents by the healthcare staff. In their time, these works were made with the intention of playfulness and experimentation rather than as meditations on mortality.

Despite the playful uses of the tropes of surgical diagrams and medical paraphernalia, cold and clinical overtones that allude to death and illness are overwhelmingly present throughout the works of Wan and Wong in this period. The exhibition is named after Wong and Fletcher’s 60 Unit; Bruise, one of the two works included in the new video Blood Brother (1976/2024), as the work’s title evokes pertinent philosophical and political questions. If we think about a unit as a means to systemically quantify, measure, and/or categorize “othered” bodies, what would it mean to bruise the unit? Would it mean to re-introduce to re-assert the human or the subjective back into the systems of oppression that characterizes hegemonic institutions and value systems? How does one puncture these naturalized visual regimes of the scientific and medical disciplines that dehumanize human bodies? By mobilizing their bodies in intensely physical works, both Theodore Wan and Paul Wong critically pose such questions while penetrating these regimes–and thus undermining their sociocultural dominance–in parallel practices that continue to remain relevant nearly half-a-century later.

Michael Dang, curator

Thank you to Christos & Sophie Dikeakos, the Vancouver Art Gallery, and Paul Wong Projects for their loans to the exhibition as well as the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory (AHVA) at the University of British Columbia, the Audain Foundation, the Capture Photography Festival, the Richmond Art Gallery and the Morris & Helen Belkin Art Gallery for their generous support.

End Notes

1. Christine Conley, Theodore Wan (Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, 2003), 13.

2. Unit Bruises is only a two-person show ostensibly, as many of Wong’s works in the exhibition are collaborations with artist Kenneth Fletcher.

3. Amelia Jones, Body Art/Performing The Subject (Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota, 1998), 9.

4. See: Jones, Body Art, 5; Cindy Stelmackowich, “Medicine’s Melancholy Mannequins,” in Theodore Wan, ed. Christine Conley (Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, 2005), 43.

5. Main Exit was located at 901 Main Street near Video Inn, then at 261 Powell Street. Wong was a founding board member of the Video Inn. Paul Wong, interview with the author, July 17, 2023.

6. Wan and Wong both participated in John Anderson’s The Gina Show, a cable access variety show that ran out of Pumps, in early 1980. Wong was a video technician at Western Front, where he often collaborated with such artists as Hank Bull and Kate Craig. See Allison Collins, “About,” Hold Still Wild Youth: The GINA Show Archive / Or Gallery, accessed November 29, 2023, http://www.theginashow.orgallery.org/about/.; Michael Turner, “Mainstreeters,” in Mainstreeters: Taking Advantage, ed. Michele Smith (Vancouver: Presentation House Gallery, 2017), 35-36; Keith Wallace, “A Particular History: Artist-Run Centres In Vancouver,” in Vancouver Anthology, ed. Stan Douglas (Vancouver: Or Gallery, 2011), 29-31, 35, 38; Wong, “Void Space: New Media (Out Of Context,” in Vancouver Art & Artists: 1931-1983 (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1983), 309-310.

7. See: Jennifer Abbott, “Contested Relations: Playing Back Video In,” in Making Video “In”: The Contested Ground Of Alternative Video On The West Coast, ed. Abbott (Vancouver: Video In Studios, 2000), 11-14; Wallace, “A Particular History,” 29-30.

8. Through his mentor Michael Goldberg’s initiatives at Video Inn, including the International Video Exchange Directory and the Matrix Video Conference (1973), Wong had access to many artists’ tapes for inspiration in this era. Wong includes General Idea, Fujiko Nakaya, and Lisa Steele etc. as early video-art practitioners that were inspirations for his own practice. See: Abbott, “Contested Relations,” 11-14; Wong, interview with the author, December 8, 2023.

9. Such prominent local personas included Lady Brute (Kate Craig), a frequent collaborator of Wong’s in this period. In addition, Wan was known under different names and aliases (i.e. Mr Normal, Ted, Theo, etc.) that corresponded to different social circles in which the artist interacted in. Scholars have connected Wan’s use of different personae to the recurring use of pseudonyms in the avant-garde, including Marcel Duchamp’s Rrose Selvay and Wan’s BFA instructor and Western Front founder Glenn Lewis (Flakey Rrose Hip). See: Grant Arnold, Kate Craig: Skin (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1998), 7; Conley, Theodore Wan, 16; Wong, “Guerrilla Television/Pirate TV,” in in Making Video “In”: The Contested Ground Of Alternative Video On The West Coast, ed. Jennifer Abbott (Vancouver: Video In Studios, 2000), 101.

10. The Viennese Actionist Hermann Nitsch visited Western Front in 1978 and a copy of a 1974 article on Nitsch was found in Wan’s archives. Joseph Beuys (in 1976) and Vito Acconci (in 1977) were notably both guest-speakers at NSCAD during Wan’s MFA studies. Burden has been mentioned by Wong as a key influence on his practice. See: Conley, Theodore Wan, 24; Garry Kennedy, The Last Art College: Nova Scotia College Of Art & Design, (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2013), 363; Wong, interview with the author, December 8 2023.

11. For his BFA at UBC, Wan studied under famed street photographer Fred Herzog as well as Lewis (see Endnote 9). See: Conley, Theodore Wan, 16.

12. Many of Wan’s works in the exhibition were made while the artist was living in Halifax. However, Wan was known to have traveled back-and-forth from Halifax to Vancouver during his MFA studies. His studio instructors included then-president Garry Neill Kennedy. See: Conley, Theodore Wan, 34.

13. While studying at UBC, Wan went under the alias of “Mr Normal” who was a man fully assimilated into Western culture donning bowler hats and other formal attire. See: Conley, Theodore Wan, 16-17.

14. Theodore Sasketche Wan, “M.F.A. Exhibition Statement, Theodore Sasketche Wan, April 1978,” in Theodore Wan, ed. Christine Conley (Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, 2003), 91.

15. Despite these attitudes, Wong describes his 1976 work 7 Day Activity (a work included in the exhibition) as a intentional insertion of himself into mainstream white beauty culture as a “pimply Asian young man.” See: Wong, interview with the author, December 8, 2023.

16. Turner, “Mainstreeters,” 34-35.

17. The advent of the handheld Sony Portapak had allowed for artists to make videos, both portably and inexpensively, and also edit in camera with cuts during shooting. See: Abbott, “Contested Relations,” 14; Sara Diamond, “Daring Documents: The Practical Aesthetics of Early Vancouver Video,” in VIDEO re/View: The (best) Source For Critical Writings On Canadian Artists’ Video, ed. Peggy Gale and Lisa Steele (Toronto: Art Metropole and V-Tape, 1996), 168; Turner, “Mainstreeters,” 35-37; Wong, “Void Space: New Media,” 306.

18. Wong’s influences from the avant-garde experimental dance scene, including Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Deborah Hay et al, can also be gleaned in In Ten Sity. In addition, later in the video, Wong is joined by the other Mainstreeters who jumped into the cube and moshed with him. See: Karen Knights, “Sculpting The Deficient Flesh: Mainstreet, Body Culture And The Video Scapel,” in Making Video “In”: The Contested Ground Of Alternative Video On The West Coast, ed. Jennifer Abbott (Vancouver: Video In Studios, 2000), 53; Wong, interview with the author, December 8 2023.

19. See: Sara Diamond, “Daring Documents: The Practical Aesthetics of Early Vancouver Video,” in VIDEO re/View: The (best) Source For Critical Writings On Canadian Artists’ Video, ed. Peggy Gale and Lisa Steele (Toronto: Art Metropole and V-Tape, 1996), 175; Wong, interview with the author, December 8, 2023.

20. Diamond, “Daring Documents,” 175.

21. See: Christos Dikeakos, interview with the author, October 16, 2023; Paul Hess, interview with the author, September 21, 2023.

22. See: Conley, Theodore Wan, 18; Dikeakos, interview with the author, October 16, 2023.

23. Conley, Theodore Wan, 18.

24. The exhibition was held at the Centre For Art Tapes in Halifax, curated by founder Brian MacNiven, and was entitled The Inversion Of The Readymade. See: Conley, Theodore Wan, 18.

25. Michel Foucault, Discipline & Punish: The Birth Of The Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Penguin Random House, 1995), 11.