Self-Winding

Paul Wong, 1988

Performance, installation

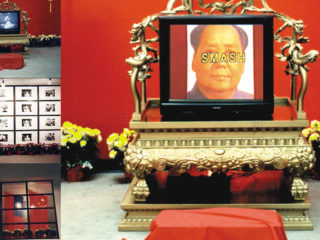

This site-specific performance/installation is a continuation of Wong’s obsessive fascination with popular culture – the seduction, allure and mass appeal of the cult figure, the reflected sense of self and the narcissistic aura of the television age. Through the use of revolving mirrored images, live and pre-recorded video, the artist constructs the means and meaning of electronic production, reproduction and evolution. History is created by projecting illusions of cultural iconography as significant references to genuine existence. In Self-Winding, the performers are integrated with mechanical and electronic devices to produce a shattered view of reality and conformity in the age of mechanical production.

Sept 23, 1988. London, England

Distributed by Paul Wong Projects

SELF WINDING – SYNOPSIS OF PERFORMANCE AND EDGE 88 FESTIVAL

SELF WINDING was a site-specific performance by Canadian artist Paul Wong commissioned by EDGE 88 – Britain’s first international biennale of experimental art. The performance took place in a disused warehouse in London’s Clerkenwell district on Sept. 23, 1988 at the specified times of 7:30pm, 8:30pm and 9:30pm. It was 36 minutes long, with a brief intermission between shows to allow for technical and performer checks. All three performances were sold out, with the maximum audience for any one show being set at 75. This restriction allowed the audience to move about within the space while the performance took place.

The performance had originally been conceived by the artist in conjunction with his artist-in-residency at the National Museum of Science and Technology (Ottawa) in July, 1988. Taking the original premise outlined by Walter Benjamin in his 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, as a starting point, Wong began working with video, media references and mirrored sculptures. These became tools to expand the Benjamin argument on photography’s status as art, to video – a medium also under attack as an art form because of its ability to be ‘mechanically reproduced’.

During his residency at the National Museum of Science, Wong supervised construction of his specially designed sculptures. The five resulting sculptures became labelled OVAL, GLOBE, CHANDELIER, PENDULUM and RECTANGLE. Each was constructed with mirrored plexiglas or glass, and fitted with a motor. The pieces were designed to function as screens for slide/video images, as well as their original purpose as sculptures. They ranged in size from 6 to 14 feet but were designed for disassembly for shipment. While the sculptures were being built, the artist also shot hundreds of slides and large segments of videotape to be edited for the EDGE 88 performance. The images varied from those readily accessible at the Museum, such as satellite dishes and transmission towers, to natural phenomena, such as lightning and thunder.

The London performance was meant to be ‘site-specific’ and ‘experimental’. Thus Wong had only a hazy idea of what it would be before arriving on site. Once he had viewed the space, the performance began to take shape. What followed was 12 days of intense construction, with upwards of 28 volunteers from Canada, England and Germany in the last few days before the performance.

Wong was assigned the main floor of a five-storey warehouse which also housed the other EDGE 88 participants: Mona Hatoum (UK), Stuart Brisley (UK) and Carolee Schneemann (USA). Although the ceiling height at 11.9 feet wasn’t high enough to fit the sculptures, the EDGE 88 committee had assigned Wong the main floor because the building didn’t have a working lift. The artist compensated for this by sawing up into the first floor to hang PENDULUM and expanding the performance space into the basement. This presented special problems, not the least of which were the lack of power and the sewage from the upper floor toilets emptying into the basement unprotected. After stopping up the toilets, Wong sent his crew down to transform the basement into what became the entrance to the performance, and the most visually stimulating area of the presentation.

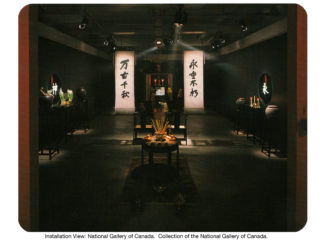

The audience entered through the main front door and was immediately shepherded downstairs by identical-looking usherettes (in keeping with a reference to the performers – four of whom were identical twins – ‘mirror image’). In the basement room (dimensions 40′ x 40′), which was darkened to allow the full effect of the video (pre-recorded and live from upstairs) projected on a 10′ x 14′ screen and monitors, the audience remained while the opening sequence of the soundtrack set a mood of opulence and decay. A single performer in a corner of the basement sounded a huge gong to accompany the thunder of the sound-track. The video images were of satellite dishes and lightning. The audience moved slowly toward a staircase on the far of the room in response to lighting cues.

Once upstairs, the disoriented audience found itself in an L’shaped warehouse which had been visually broken up into various settings. There was no one focal point. To the left was a 12′ diameter chandelier made of shards of broken mirror, which began to spin, slowly at first but then more menacingly. Behind it, a hooded figure with mirrored eyes and mouth began swinging PENDULUM- with its 5′ diameter mirrored rotating saw blade. At this point, both sculptures were covered in white foam core to allow their use as screens.

To the right, a male martial artist/performer began going through his poses on a raised rotating turntable, only to be replaced seconds later by a male opera singer, clad in all-white. Opposite to this, one of the male identical twins was lifting lightweights (literally bar bells with rotating police lights on either end). The soundtrack was muted to allow for the clear resonance of Gluck and Puccini, while the live video camera focused on the singer’s face projected on the 10′ x 14′ screen on the opposite side of the room. As the operatic portion died down, the audience was drawn to OVAL, set up beside the video screen, which now began to spin in its frame. It too was covered with white foam core for projection, but now this was removed by the female identical twins who became ‘mirror images’ on either side of the double-sided looking glass. The video images changed rapidly from those of popular culture, appropriated clips from Wong’s previous tapes Prime Cuts and Homelands, to that of a statuesque black model looking puzzled at the audience, cut with live footage of the martial artist now back on the rear turntable. The hooded performer in front of PENDULUM waved a huge white flag which became a projection screen for other video/slide images.

As all the machines were starting up, the martial artist created Another sound/light force with a metal grinder on one of the gold-painted columns in the middle of the room. A female twin swung GLOBE toward the audience, creating a searchlight effect whenever the mirror caught one of the overhead lights. The male twins, both on the front turntable, stroked each other with CCD minicams, creating the illusion that they were photographing themselves.

The focus shifted to a female Red Guard on the rear turntable. She held aloft a machine gun and stared vacantly at the audience while she turned. A female saxophone player strolled through the audience and took up position at the rear of the large screen. A female twin lay seductively on a chaise lounge to the left of the screen. Popular culture images of Hollywood, JFK and the Duchess of Windsor filled the front and side screens, while a male twin shaved half-naked in front of a mirror to the right. RECTANGLE, a 4′ x 8′ double-sided mirror on a precarious frame, started up and the saxophonist transformed into a stripper behind it.

At this point, all the performers and machines were moving. The Red Guard transformed into the Material Girl and made her way through the audience with a ghetto blaster playing Madonna’s “Material Girl”, into the room with PENDULUM and CHANDELIER. She knelt in front of a fan and strobe light with fluttering rose petals in her face, an image which was projected on the large screen behind her. The male/female twins changed partners and were paired off in boy/girl couples on opposite turntables. The opera singer was in front of a side mirror singing to his own image. CHANDELIER picked up speed and whirled erratically with its shards of 5″ broken mirror on chain swinging out 3 feet.

The performance ended anti-climactically as the singer smashed the mirror in front of him. The soundtrack and machines simply stopped. The images were turned off and the house lights brought on.

Throughout the performance, Wong directed the 10-person technical crew via clear-com headsets. At various times, his instructions could be heard during a lull in the soundtrack, giving the audience the impression that they were backstage. In addition, the constant moving about by both performers and crew, within and around the audience, dispelled any notion that there was a clear ‘stage’ or only one sight-line. The audience was left with a feeling of having been part of the performance and involved with technical aspects usually hidden backstage in more conventional performances.

Postscript

The ultimate intention of this project, other than producing a strong performance, was that there would be a video document at the end of it. The pre-recorded video, and that recorded at the performance, will be combined and edited to produce a videotape of SELF WINDING. The 450 slides taken for the performance. will be amalgamated the 20 rolls taken on set of the set-up, performance and aftermath. There will be a monograph of the piece which will likely take the form of an artist’s book. At time of writing, the artist was still formulating the process/format that this document will take.

SELF WINDING – Within the context of the EDGE 88 Festival

It was agreed by all other participants and the organizers that in terms of scale, SELF-WINDING was the most ambitious performance in the festival. Almost all the other performances involved just the artist as performer. In those where there were more performers, the technical aspects were minimal. SELF WINDING had both numerous performers and complicated tech. This is not to say that just because SELF WINDING was the biggest that it was therefore the best. Rather, that Wong was able to expand his vision of performance to the maximum and create a large-scale, technically demanding piece, involving North American and European power requirements, with intricate shipping arrangements from Ottawa, Vancouver and Newcastle to London. He was able to retain the essence of the work’s concept, while somewhat fetishizing the machines used, and create a successful performance.

Aside from aesthetic concerns, the piece was culturally progressive, in that there was tremendous local art community involvement in producing it. As seen in the programme, there was a large complement of volunteers as well as assigned EDGE 88 workers. Everyday there were new people arriving on site volunteering to do the most mundane tasks. This was partly because word had spread that SELF WINDING was so large-scale and had state-of-the-art video equipment, but it was also the enthusiasm generated through the process of transforming the space, especially the basement, into its site-specific performance requirement.

The local community success of the performance can be judged by the audience response. Before it, Paul Wong was the least-known artist, in Europe that is, on the EDGE 88 roster. His name was not a particular drawing card but has become so now, evidenced by his sold-out screening in Newcastle the following week.

DIRECTOR: PAUL WONG

PRODUCTION MANAGER: ELSPETH SAGE

SITE COORDINATOR: COLIN GRIFFITHS

DEVICES: DAVID JACKSON

VISUALS: JOE SARAHAN

STAGE MANAGER: SUSIE MILNE

COMPOSER: STEPHEN ROSEN

PERFORMERS

Sean Conrad Dower – martial artist (#2)

Carole Jackson – female twin

Christine Jackson – female twin

Paul Jones – opera singer

Tom Radcliffe – martial artist (#2)

Kumiko Shimizu – Red Guard

Georgia Varjas – saxophonist/dancer

Guy Waddell – male twin

Mark Waddell – male twin

PRODUCTION PERSONNEL

Daina Augaitis (Banff)

Tara Babel (London)

Steve Collins (Newcastle)

Laurence Counter (Cornwall)

Sean Dower (London)

Bruce Gilchrist (London)

Colin Griffiths (Banff)

Oliver Hardt (Giessen)

Mona Hatoum (London)

Kirsten Herkenrath (Giessen)

David Jackson (Vancouver)

William James (London)

John Jordan (Sheffield)

Attila Lukacs (Berlin)

Susi Milne (Vancouver)

Tom Radcliffe (London)

Chick Rice (Vancouver)

Stephen Rossin (Vancouver)

Paddy Ryan (London)

Elspeth Sage (Vancouver)

Joe Sarahan (Vancouver)

Jason Skeet (Stoke-on-Trent)

Guy Waddell (Stoke-on-Trent)

Mark Waddell (Oxted)

Jeff Ward (Stoke-on-Trent)

Sally Whitman (London)

Steve Williams (London)

Andrew Wilson (London)

Thomi Wroblewski (London)

SELF WINDING was a special project of ON THE CUTTING EDGE PRODUCTIONS SOCIETY.

PROJECT DEVELOPED BY THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (OTTAWA).

PARTIALLY FUNDED BY CANADIAN HIGH COMMISSION (LONDON), CANADA COUNCIL (MEDIA ARTS, VISUAL ARTS & ARTS AWARDS), DEPARTMENT OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, EDGE 88, B.C. CULTURAL FUND.

PRODUCED BY ON THE CUTTING EDGE PRODUCTION SOCIETY.