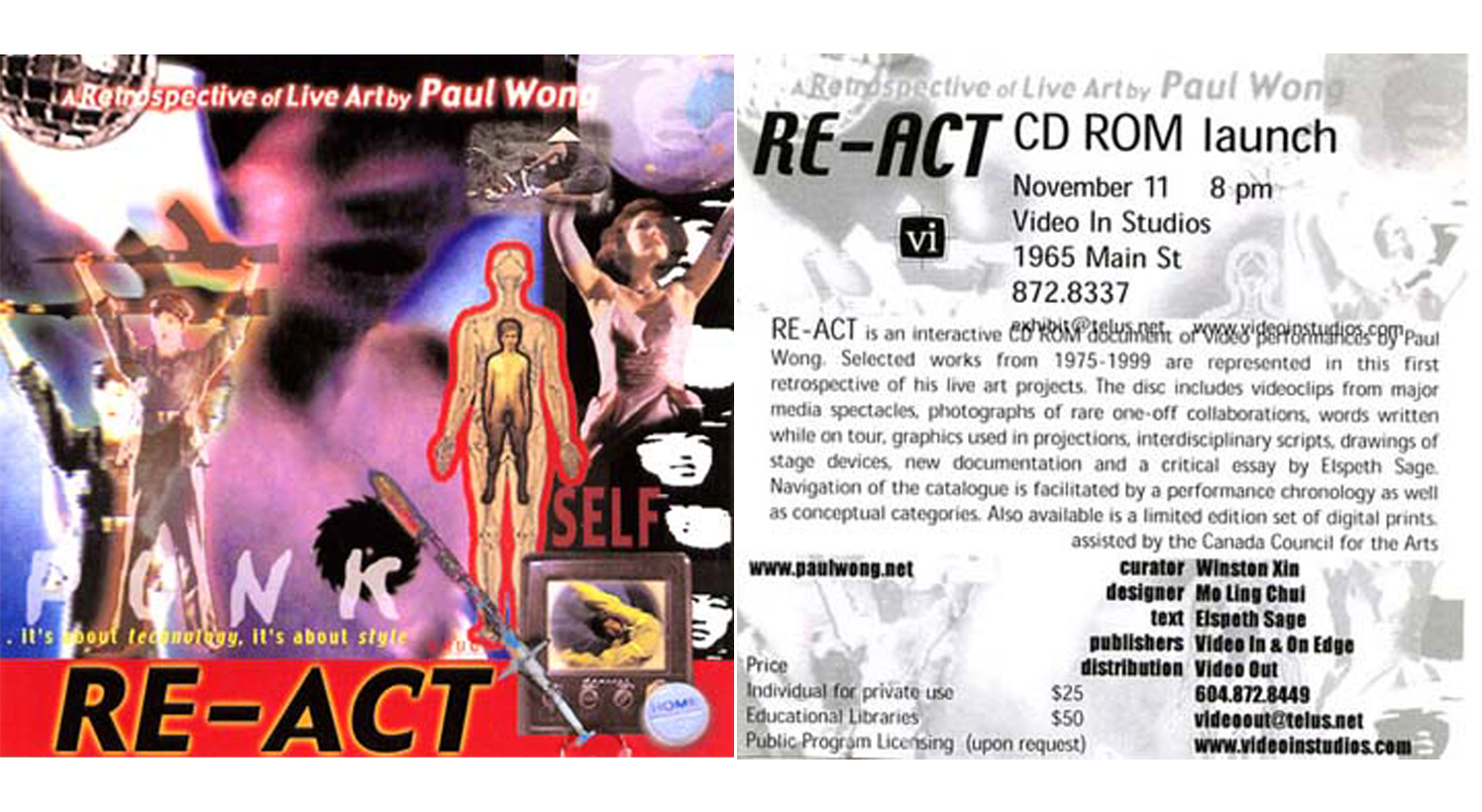

Re-Act CD-Rom

Paul Wong, 2001

Released in March 2001, Re-Act is an interactive CD Rom document of video performances by Paul Wong. Originally produced by Video In for Live At The End of The Century Performance Art Festival Vancouver in November 1999. Selected works from 1975-1999 are represented in this first retrospective of his live art projects.

The disc includes videoclips from major media spectacles, photographs of rare one-off collaborations, words written while on tour, graphics used in projections, interdisciplinary scripts, drawings of stage devices, new documentation and a critical essay by Elspeth Sage.

Navigation of the catalogue is facilitated by a performance chronology as well as conceptual categories. Also available is a limited edition of digital prints. Assisted by the Canada Council for the Arts. On Edge & Video In publishers.

Anatomy of a Thriller

by Elspeth Sage

from the National Gallery of Canada catalogue

Paul Wong: On Becoming a Man (1995)

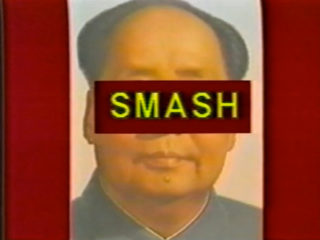

The central theme of Paul Wong’s performance work is his trademark style of going to extremes. The artist is fearless and unblinking, forcing the audience to grapple with his view with the same energy with which it was created. He portrays an all-or-nothing attitude, not in a gratuitous sense but rather of necessity. His is an intensely personal world laid public for all to see, or see through. Coupled with this, there is an ambiguity of whether the view is really a personal one at all. He has at times displayed a confusing reverence for and abhorrence of cultural status symbols and qualifiers, leaving it up to the audience to decide where to go from here. He has singlehandedly turned superficiality into a work of art.

In his many performance pieces over the last twenty years, he has provided a glamorous, and sometimes annoying, focus on the banal through consistent presentation and rearrangement of popular culture icons. It is the constant duality of profundity and vacuousness ever present in Wong’s work that has defied classification and resulted in an unusual divergence of opinion amongst contemporary critics regarding his productions. There is an ever-present play in his work. He vacillates between fiction and non-fiction in the positioning of a biographic portrayal of those close to him with the ostensibly autobiographic images of the artist himself, and between live versus prerecorded performance. His is a world of non-linear, non-text, action-based work. His scope is multi-media with an astonishing diversity of elements, from the organic (roses, incense, earth, candles, cedar trees, oranges, bottles of Scotch), to products that characterize the twentieth century (mirrors, motorized devices, M16 rifles, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, welding kits, and state-of-the-art digital technologies).

In his many performance pieces over the last twenty years, he has provided a glamorous, and sometimes annoying, focus on the banal through consistent presentation and rearrangement of popular culture icons. It is the constant duality of profundity and vacuousness ever present in Wong’s work that has defied classification and resulted in an unusual divergence of opinion amongst contemporary critics regarding his productions. There is an ever-present play in his work. He vacillates between fiction and non-fiction in the positioning of a biographic portrayal of those close to him with the ostensibly autobiographic images of the artist himself, and between live versus prerecorded performance. His is a world of non-linear, non-text, action-based work. His scope is multi-media with an astonishing diversity of elements, from the organic (roses, incense, earth, candles, cedar trees, oranges, bottles of Scotch), to products that characterize the twentieth century (mirrors, motorized devices, M16 rifles, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, welding kits, and state-of-the-art digital technologies).

He has consciously crafted work to make an impact in a defiant way that eschews, and often ridicules, complacency. Unlike many artists who create performance, Wong is concerned with a visceral audience response rather than any nod to the ironic. More than anything, he wants us to be seduced. He strives for cultural relevance and carefully avoids the contrived academic posturing that has invaded so much of post-modernism.

Dating back to the early 1970s, Wong has viewed public appearance from the perspective of a central credo to create tension. Over the years, the subject matter changed but the methodology remained the same. His video and live work are both created in an environment that is sometimes painfully honest, and produced not simply to shock but as a natural result of his way of viewing the world. “Paul Wong is a Vancouver incarnation of Kafka’s hunger artist, a self-consuming image maker who goes right to the bone in ways that are shocking, piercing, and transfixing.”1

Wong has harnessed the ability to open his veins for his art, hence the often virulent criticism he has received for being too outrageous. An early example of his ardent subjective involvement in his work was aptly titled in ten sity (1978). “Unlike the majority of his works, there was no detachment on the part of the artist here, only, as the title indicates, intensity, The audience, on the other hand, was again allowed only a voyeuristic view of a private experience.” 2

Wong’s work has always been a reflection of his times, of a thrill-seeking popular culture that constantly desires new pleasure/pain/fear stimuli. While still in his teens, he began to produce work – for and with the video camera – that provided a view, sometimes awkwardly close up, of what it meant to be young, angry, immature, tough, and raw in a world that seemed hopelessly out of control. His own life proved verdant ground for material, and he had no compunction about sharing his experiences and those of his immediate circle with the general public. In 1980, he made “4″ – a national touring show in which Wong himself appeared. It was later produced as a videotape so gritty it was hard to watch, then and now. This work was described by John Bentley Mays in a 1980 review:

“4″ charts the tension and affection that mark the relationship of four women (who play themselves and caricatures of themselves, throughout). Occasionally acid, sometimes charming, always fresh, “4″ nevertheless has emotional impasse as its bottom line. The performance’s final image, four women helping each other home after a dead-end evening of drinking and dancing, is one of loneliness and isolation. But if Wong is working true to form, this work is also a rite of seeing things out properly – a miniaturisation of his friends in this dramatic context, as a strategy for transcending them. It will be interesting to see what this trickster, shaman, soul doctor of art does next with his remarkable powers.3

Wong had earlier discovered that self-expression could be a vehicle for healing, as in the performance of in ten sity. This piece was to provide a catharsis for a close friend’s recent suicide. It was performed at the Vancouver Art Gallery before a capacity crowd and documented from five separate camera angles, later to become a videotape. “in ten sity was the result of pure power. And power is an energy that Wong thrives on as he spreads the presence and his art into an energetic and hyped personal expression.”4

In a performance “for the camera,” in 1976, entitled 60 UNIT: BRUISE, he reflected the dangerous and daring aspect of his age and times. Here the camera is focused on Wong’s back while 60 units of a friend’s freshly-drawn blood is injected subcutaneously into him. The camera captures the image of a slowly-emerging bruise as the blood enters Wong’s body. It is shot in real time and ‘in-camera edited’ – with no apologies or special effects.

From the outset, he instinctively joined and readily embraced the developing dialogue that viewed performance as anti-object art-making and the creation of a new media language. As a young teenage artist, Wong was fascinated by and yet critical of the new art movements happening around him. Even in his first works, it was obvious that his sensibilities in art terms were original. The significant cultural differences between the artist and the art world he had begun to inhabit were evident even then, but would only be truly manifest much later in his career.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, his work did not display the jocular, tongue-in-cheek aspects prevalent in 1970s performance art in Canada, and in Vancouver in particular. In fact, Wong exhibited a conscious rejection of late 60s and early 70s tendencies of performance artists in such groups as Intermedia and the Western Front to create personas and a.k.a.’s, for example Dr. Brute and Lady Brute, Mr. Peanut, Marcel Dot, and other Dada and Fluxus-inspired identities. He was somewhat annoyed with the humour of those other works, and certainly his own products from that time were devoid of the silly irrelevancies that motivated much early performance work.

Instead, he was more directly influenced by the serious conceptual, site, earthworks, and body artists such as Robert Smithson, Chris Burden, Richard Serra, Joan Jonas, Lisa Steele, Herman Nitsch, and such alternative image makers as his personal mentor Michael Goldberg, D.C.T.V., Alan and Susan Raymond, Rodney Werden, Pierre Falardeau, and pop artists Andy Warhol and General Idea. Perhaps the strongest influence on his early work came from the arte povera movement begun in the 1960s, with its use of found objects and humble materials.5 Unlike many emerging artists in the mid-70s, Wong did not come from a privileged background, and this may account in part for his proclivity for this particular form of art-making.

Among his early visual sources were Radical Software, GQ Magazine editorial spreads from the 1970s by Bruce Weber, Interview and Avalanche magazines, and advertising in general. These images are continually referenced even now and have provided the core script visuals for most of his performance work. He uses this material with irony – as unattainable yet ultimately desirable. He is unabashed in his support of consumerism and delights in presenting it as an alternative to the perennially starving artist world.

An essential element of Paul Wong’s performance and video work has been a concern with the soundtrack, bordering on obsession. In this, he is very much a product of his times, where the musical revolutions of rock and disco, punk, new wave, techno rap, house, etc., have completely permeated youth culture, and in fact, culture in general. In Wong’s work, the audio and visual are essentially linked. One will not be properly conveyed without the other. He credits as his musical influences the Velvet Underground, T-Rex, Yoko Ono, glam rocker David Bowie, disco queens Gloria Gaynor and Donna Summer, Ike and Tina Turner, punk rockers Patti Smith, The Sex Pistols, The Avengers, and Throbbing Gristle, new wavers like Talking Heads, Brian Eno, and Laurie Anderson, to more recent favourites like Prince, Moist, and U2. 6

In fact, the genus of the visual imagery, and certainly the timing, is almost always determined by the music. The performance staging is done cue to cue with the sound. Wong’s works are invariably accompanied by original, specifically commissioned sound components, often produced by Vancouver composers Steve Rosin and Gary Bourgeois. He has consistently been aware of music’s seductive powers, and has intentionally played with the obvious coinciding relationship between his work and the medium of the music video.

His passion for the banal and vacant aspects of television culture has often been misunderstood by critics. Peter Culley, reviewing Wong’s work BODY FLUID in 1986, stated: “The wilful naivete and directionless facility of Wong’s work call to mind the ideology of the rock video, which hung heavily over the evening’s proceedings. The performance managed to combine most of rock video’s faults while containing few of its virtues. The concision and wit of the best rock video was noticeably absent, and the numbing music and smokebomb/leather/motorcycle imagery was reminiscent of heavy metal at its worst.”7 Rather than containing any insightful commentary on Wong’s work, these words display an inability to grasp the essential function and true nature of rock videos. That critic also appears ignorant of the artist’s intent and his popular appeal. The performance worked, and precisely for the reasons that Culley derided it. A second performance of BODY FLUID had to be run after the first show sold out, testifying to its success with the audience.

Wong makes a distinction in his productions by consciously using the term “live” rather than “performance” to delineate what he does.8 He points out that there is a difference between live works done “for the camera” and those not, those produced as a document of a performance, and performance presented with a videotape component. Many of his videotapes were released in a performance context. To blur this distinction even further, his live pieces often include self-documentation of the performance by the performers – through the use of mini-cams on stage or attached to their bodies.

His work has always been primarily influenced by the specificity of “site” and an interest in non-gallery venues. Wong’s locations have included shop windows, public transit shelters, cabarets, warehouses, offices, ice rinks, artist-run centres, ballrooms and discotheques. This importance of site as a motivator was illuminated by Keith Wallace in a review of BODY FLUID (1986):

The ramp that descends to the Sears Parkade in downtown Vancouver and terminates at a giant truck turntable was the setting for Paul Wong’s video performance/installation Body Fluid. It was a fitting location for a spectacle based around popular culture mythology, down in the guts of a major department store and a host of 48 other stores that make up the one-stop shopping of Harbour Centre Mall. The turntable, a good 30 feet in diameter, is the delivery point for masses of consumer goods that are pumped into the stores and bought up by a public fed by the advertising media.9

The concern for the multiple readings of the use of a site, and the possibility that a passive exhibition such as INSTALLATION 1984, at the Convertible Showroom in Vancouver, could be viewed as a performance piece was elaborated by Wong, who characterized it as “an exhibition but also as a set. I was very aware of the street traffic seen through the windows, and by presenting barbed-wire sculptures inside the gallery I intended to create an element of danger and anticipation outside.”10 This work is one of the few that does not include a video component.

By the early 1980s, Wong’s live work developed naturally into large-scale spectacles. His fascination with technology and growing access to larger budgets saw the production, in 1983, of the first of three aspects of the CONFUSED projects, namely CONFUSED: THE PERFORMANCE. It was described by Wong in a later interview as “a one-off work of ‘performance art’ that took place 4 November 1983 at Toronto’s Video Culture festival, sponsored by the Sony Corporation. Director Wong performed with co-producers Jeanette Reinhardt, Gary Bourgeois, and Gina Daniels. Most of the time they wore clothes. The TSO performance got little ink because of the press’s inability to score tickets.”11 It included a large cast of both actors and crew, combined with live and prerecorded video and sound, as well as a plethora of visual stimuli. In many ways, it marked a turning point in the nature of Wong’s live work, in that his reliance on technology and special effects came into its own in this production.

An even larger-scale production was presented on 2 March 1986, as part of the video and performance exhibition Luminous Sites in Vancouver. Wong’s work, entitled BODY FLUID, has been briefly discussed in terms of site. The curators summarized the content and motive for the work in their catalogue essay as “rituals are the hollow gestures of prime time.”12 The images in BODY FLUID all found their inception on television and were presented in a layering method very similar to the rock video format. It was frustrating for an audience looking for an explanation where there was no overt message.

In 1988, as artist-in-residence at the Museum of Science and Technology in Ottawa, Wong had his assistant David Jackson build five large mirrored motorized sculptures in the forms of a chandelier, globe, oval, two-way rectangle and pendulum. He had begun work on SELF-WINDING, his most challenging and complex spectacle to date. The scale was vastly extended, both in terms of personnel, technology, and especially location – an abandoned warehouse in London, England – as part of Edge 88, Britain’s First Biennale of Experimental Art. A press release depicted it as “a site-specific performance on the seduction, allure and mass appeal of the cult figure, the reflected sense of self and the narcissistic aura of the television age.”13

Despite the artist’s claim that the spectacle was “very close to being a multi-media mess,” SELF-WINDING was a success. Yet it almost became a victim of its own ambitious technical challenges, dense choreography, and large cast. One onlooker commented, “I suppose one could go to Disneyland and see the whole experience as a political statement about the unrelentingly mediated existence we live. But even with a statement to that effect at the gate, how many would? Tourists just wanna have fun,”14 As had happened so often in past works, Wong had once again set the audience up with unrealistic expectations and unrealizable goals, only to have them recognize at the end that there were no answers here,

After a five-year hiatus from live presentation, Wong made CHINAMAN’S PEAK: WALKING THE MOUNTAIN in 1992, as part of the Race and Body Politic residency at the Banff Centre, in Alberta. Once again, the work was multifaceted and became a performance, a videotape, and an exhibition. After an outdoor performance in Banff, where the artist and his audience literally “walked the mountain” to perform the ritual of ancestral worship, the work became a single-channel videotape, and finally a video installation at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver in January 1993. It was later presented in all three forms as part of Feng Shui, a video and photography installation, in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in September 1993. Wong outlines the nature and content of his performance:

Walking the Mountain refers to the beliefs and rituals associated with ancestral worship and respect for the dead. The performance utilised the graveyard of All Saints’ Church and consisted of traditional and additional rituals and elements associated with ancestral worship. These were performed at some of the selected grave sites. Rituals at gravestone included tending of the grave site: demarcation, grave sweeping and the placement of candles on the tombstones. The elements of fire, earth, air and water, smell, taste, noise and visual components were included.15

CHINAMAN’S PEAK signalled a marked departure from the loud, vibrant, complicated, and techno-driven performances of the 1980s. The elements were simple, organic, and silent, referring to a respect for message over medium not seen in Wong’s work for decades. The works had come full circle.

The banality and over-eager consumerism so often reflected in his earlier works had been abandoned, just as it had been in the 90s’ societal philosophy that reviled the 80s’ decadence and empty greed. Instead of looking inward and finding an enduring passion to escape, make better, and consume, Wong presented CHINAMAN’S PEAK as a spiritual journey that became a literal entity in his performance of the haang san (walking the mountain) ritual. As with in ten sity, the theme of this work was death and the artist’s method of dealing with it. Whereas the early performance had been motivated by frustration and disbelief, this time the process produced calm reconciliation and quiet acceptance.

More recently, his work has become sober, sophisticated and calculated. His passion is no longer that of an alienated youth but that of a dedicated artist, just as tough as the youth ever was, but without the anarchistic attitude characteristic of the 1970s and 1980s. Like his audience, Wong has never been content with the normal or mundane. Over the past two decades, he has created a niche that provokes certain expectations in the local and national art world, to be constantly questioning and opposing the status quo.

Notes

1 Peter Wollheim’s review in Vanguard, 9:3 (April 1980), pp. 23-24.

2 Steven Durland, “Three Points in a Circle: Three Decades of Experiment in the US and Canada” Edge 88 (exh. cat.), London: Edge 88/Performance magazine 1988, p.19.

3 John Bentley Mays, Globe and Mail (Toronto), 26 Feb. 1980, p. 15.

4 Arthur Perry, Arts Magazine, 10:43/44 (May/June 1979), p. 44.

5 Arte povera (Italian: “impoverished art”), a term coined by the critic Germano Celant to describe art produced in minimal formats and with deliberately humble and commonly available materials, such as sand, wood, stones, and newspaper. Dictionary of Art Terms, London: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

6 Conversations with the artist.

7 Peter Culley’s review in Vanguard, 15:3 (Summer 1986), p. 40.

8 Conversation with the artist.

9. Keith Wallace, “Body Fluid (1986),” Video Guide, 8:2, issue 37 (Spring 1986), pp. 6-7.

10. Conversation with the artist.

11. Les Wiseman, “Video Gaga” Vancouver magazine (June 1984), pp.30-36.

12. Daina Augaitis and Karen Henry, “Retrieving Culture” in Luminous Sites, Vancouver: Video In/Western Front, April 1986, p. 52.

13. “On Edge (Vancouver)” press release for the Edge 88 Festival, London,

31 Aug. 1988.

14. Steven Durland, “Throwing a Hot Coal in a Bathtub” High Performance, Los Angeles, 11:4, no. 44 (Winter 1988), p. 34.

15. Paul Wong, “Artist Statement,” in Elspeth Sage, ed., Feng Shui (exh. cat.), Vancouver and Newcastle,upon,Tyne: On Edge/Locus +, 1994, p. 31.