Camp Potlatch

Camp Potlatch Reenactment, Kenneth Fletcher (1976)

Paul Wong, 2015

HD video, stereo sound, 4:00 min

This is a re-staging of Kenneth Fletcher’s original for-the-camera performance in 1976. This performance was based on a handful of black & white photographs taken by Paul Wong. This was re-staged as a live event for the Mainstreeters: Taking Advantage 1972-82 exhibition at the Satellite Gallery, January 22 2015, curators Allison Collins and Michael Turner.

Camp Potlatch is the name of a wilderness camp operated by the non-secular Boys and Girls Clubs Society in Vancouver. “A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States” (Wikipedia). This performance is based on an action that Fletcher learned at camp, a simple blood letting ritual involving the use of a comb. This intimate gesture considers the social, economic and political connotations of the camp and its place in Fletcher’s imagination. This action has been updated through a re-enactment by aboriginal performer Edwin Neel.

Tommy Chain, Paul Wong, Edwin Neel, photo by Merle Addison

Available from Paul Wong Projects

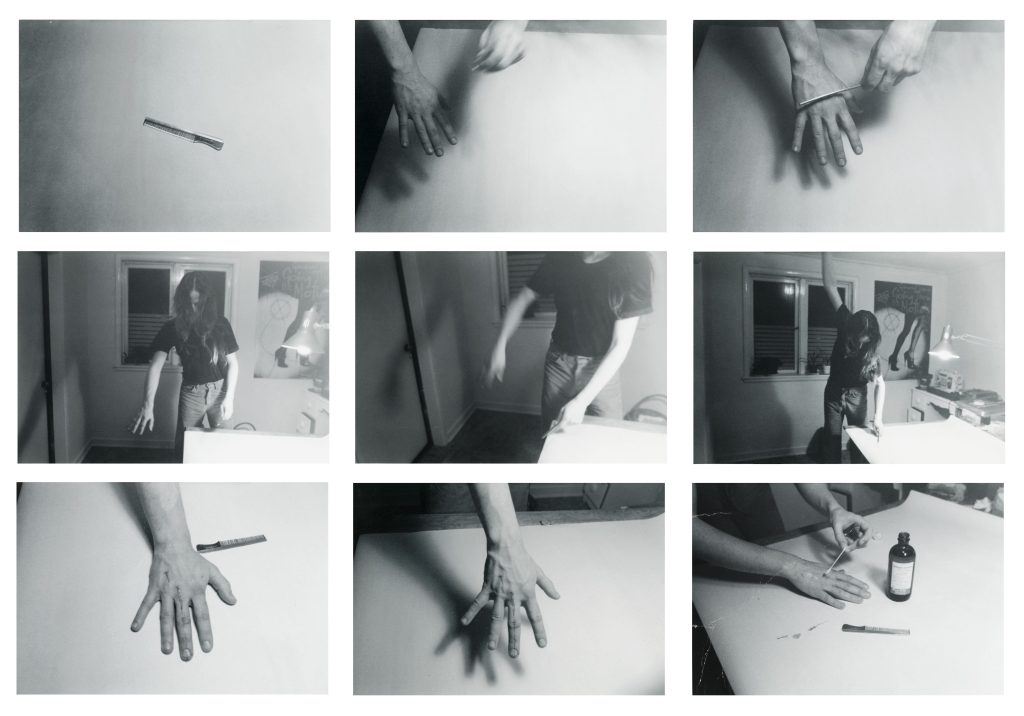

Camp Potlatch, 1976

Conceived and performed by Kenneth Fletcher

Video Paul Wong, 1976

Produced at the Western Font

excerpt from:

SCULPTING THE DEFICIENT FLESH

mainstreet, body culture and the video scalpel Karen Knights

Edited by Jennifer Abbott. 2000. ISBN 1-5512-022-2

In Camp Potlatch, Ken demonstrated a procedure of “self‐mutilation” he learned at a summer camp of the same name.9 A metal comb is used to cut the back of the hand, then the arm is swung repeatedly in a wide arc until blood flows. Shot on the inside of “Watson Strasse,” Jeanette and Paul’s early home, the domestic scene seems incongruent with the act. The title alone remains to evoke the fraternal mystery and daring inherent in the original action. This simple act is crudely imitative and resonant with meanings ascribed to ceremonial blood rites where the ritual of cutting is commonly considered first a rite of separation but also ultimately one of incorporation and/or empowerment. As a rite of passage it marks the transition (physiologically and/or psychologically) between boyhood and manhood. In Western culture characterized by secularization, urbanism and scientism, ritual rarely includes the actual cutting of flesh (the Jewish briss being an important exception) but rather functions through symbolism, and even then (as in marriage ceremonies) is often reduced to empty habit rather than effective (meaningful) ritual.

I use the term “self‐mutilation” in defining Ken’s action precisely because of its moral connotations and its cultural and historical specificity. It is a term common to anthropological investigations into the exotic Other and in Western psychiatric practice. It is most often used in reference to actions taken by those considered “foreign” to this society and its dominant belief system. It reflects a belief in a “naturalized” body which in turn requires us to delimit the marking of the flesh, to draw a line between acceptable and unacceptable body alteration. There are always, however, subgroups inventing new rituals for themselves or appropriating those of other cultures. The growing popularity of body piercing and tattoos are two examples. In the case of adolescents, some sociologists argue that the need for formal markings of life passages, especially puberty, is so important that in the absence of effective societal ritual, the adolescent is driven to create his/her own.10

Certainly almost all children have at some time taken part in rites similar to the one Ken demonstrates. In the case of child‐initiated rite, as opposed to those sanctioned by society and facilitated by adults, the action will occur anywhere from a rec room, a fort, or other hideaway where children have prolonged exposure to one another away from adult supervision and where those fickle and complex bonds of childhood friendship are made and broken. That the action taken at Camp Potlatch originally occurred in secrecy and the relatively “wild” surroundings of a summer camp ties it to the other initiations which often occur in uninhabited sites, the removal of the child form the social space (and especially mother and other women in male ceremonies) bring an important component. In his video, however, Ken positions himself somewhere between initiate and anthropologist reenacting as well as recording the elements of the rite. Removed from both the original location and age when it occurred, he provides the necessary distancing for us to be less voyeurs than students of the process.

9 As a copy of Camp Potlatch has not been found, my comments are based on photo documentation of the piece and my interview with Paul Wong.

10 Edith Sollwold, “Ritual Maker Within at Adolescence.” In Betwixt and Between: Patterns of Masculine and Feminine Initiation. Edited by Louis Carus Mahdi, Steven Foster and Meredith Little (Open Court, Illinois, 1987). Some activities identified by anthropologists as Western male initiations include the stag party, sports ad related social activities, such as drinking and the cult of the automobile, where acts of machismo are expected and reinforced.

Camp Potlatch Photography 1975

Paul Wong, 1975

photo, video, performance