限华 / Chinese Only

Paul Wong, 2018

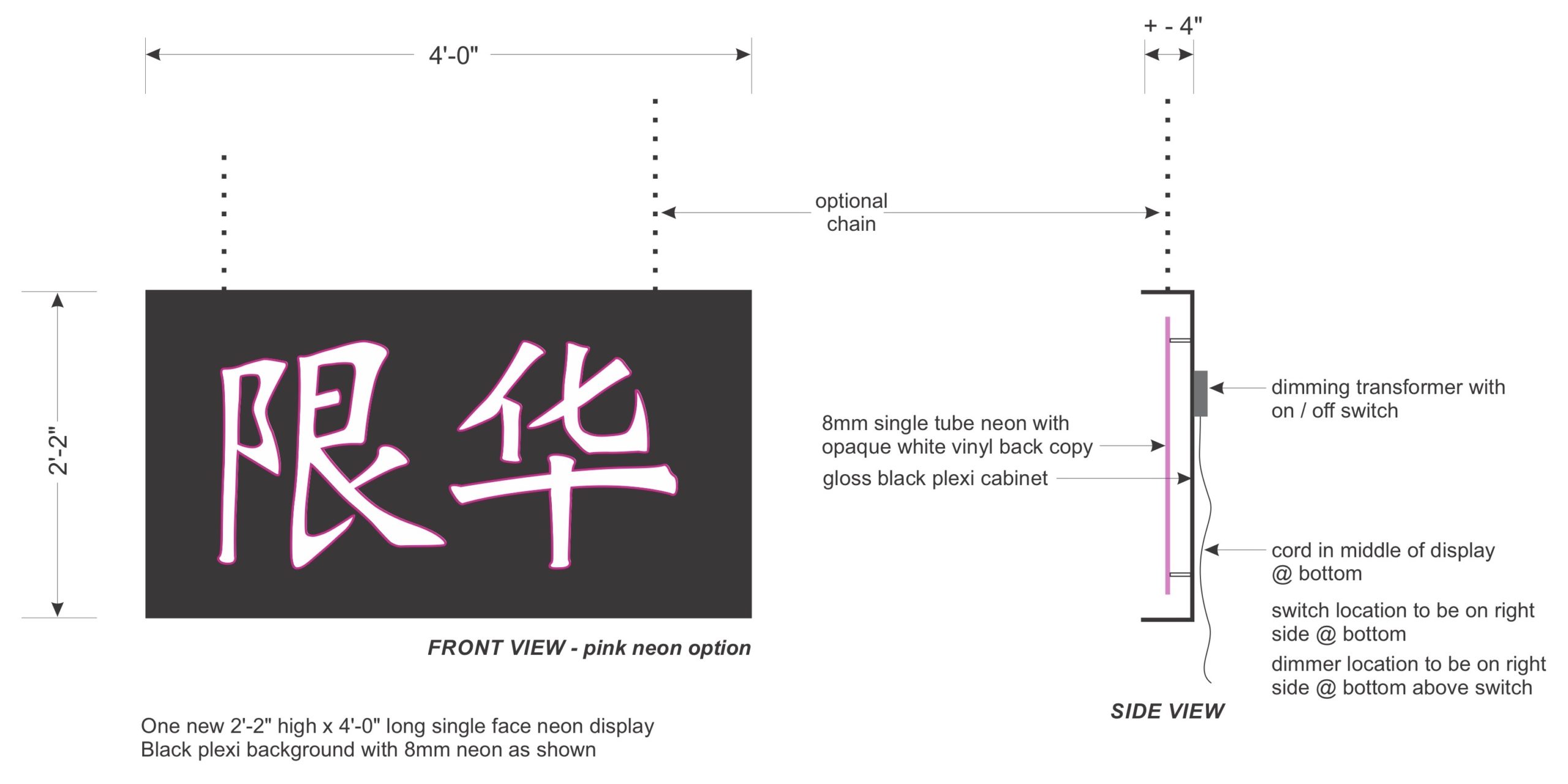

Neon sculpture, 48″ x 26″ x 4”

Glass, plexiglass, electronics, metal

Available for sale:

限华 / Chinese Only Pink, 1 of 1

限华 / Chinese Only Yellow, 1 of 1

Inquire admin@paulwongprojects.com

In simplified Chinese Characters, 限华 / Chinese Only is a new neon artwork series in Chinese characters. Each neon piece is unique, it is available in pink, red, white and yellow neon with white graphics on black box. Each work is CSA approved with on/off switch, dimmer and signed on the back.

限 translates to “limit”, and 华 translates to Chinese. 限华 / Chinese Only takes the form of a ‘sign’ where it references a time when local white-only establishments blatantly refused and restricted Chinese people. The sign, however, can also be interpreted as “Chinese Exclusion” as, the characters 限 and 华 are often used to describe the country’s historical exclusion of Chinese people.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, (the Act) was a 1923 act passed by the Parliament of Canada, banning most forms of Chinese immigration to Canada. Immigration from most countries was controlled or restricted in some way, but only the Chinese were so completely prohibited from immigrating. The act was repealed in 1947.

Chinese Only is part of a series of new works being created and inspired by Wong’s relocating his studio in early 2018 into the heart of historic Chinatown in Vancouver. A Chinatown that is undergoing rapid gentrification by non-Chinese businesses and dwellers in an area that had been almost exclusively occupied by people and things Chinese.

This work was part of Occupying Chinatown, Paul Wong’s year long residency at the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Chinese Classical Garden. To see the rest of the works curated for this visit:

“External advertisement materials like large box and illuminated signs, raised letters, awnings, banners, and neon signs, used by Chinatown stores and restaurants to entice customers with “Oriental” iconography or exotic fonts, also contribute to the formation of a Chinese space and identity. Paul Wong’s 限华 / Chinese Only neon sign references the “Chinese Exclusion” era, when white-only establishments blatantly refused entry to Chinese people. At the same time, legislation was passed that imposed a head tax on all immigrants from China and banned most Chinese from entering Canada. Yet Wong’s piece can also be an interruption to the idea that Chinatown is a ghetto. And especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when, due to the association of the virus with China, racist attacks on Chinese individuals and vandalism of Chinatown buildings and gate lions have made residents feel unsafe in their own neighbourhood, the neon is an offer of a “Chinese only” safe space-a sanctuary.” – Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections, Griffin Art Projects, 2021, P18

“Other intangible concepts, like racism, undoubtedly harm yet also shape responses of resistance, community support, and, inevitably, one’s identities. How does one perform oneself, one’s citizenship, one’s belonging-and how does this shift according to the spaces and contexts one finds oneself in? Paul Wong’s neon sign, 限华 / Chinese Only (2018), references a time when white only establishments refused service to Chinese people. The sign can also be interpreted as Chinese Exclusion, where 限 translates to “limit,” and 华 to “Chinese.” It recalls ongoing debates about Chinese-only signage in Richmond, British Columbia, since 2013, with council voting 5-4 in 2017 in close favour of a non-enforceable “clutter bylaw,” which mandates that signs include a minimum 50 percent of one of Canada’s official languages, and that sandwich boards and window signs be reduced in number 17. This, despite the immigrant population of Richmond being over 60 percent, of which 50 percent identify as Chinese, with only 3.5 percent I of all signs in Richmond tabulated as Chinese-only in 2015.18 Some argue that the bylaw is an act of veiled racism and a breach of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Others, such as Mayor Malcom Brodie and Councilor Chak Au, who both voted against the bylaw, point to the cultural tensions beneath these public debates and the need to work together to find solutions. There are varied limits to tolerance, it seems, tested at historical moments.

“Chinese Only” has multiplicities of meaning: as Karen points out, segregation was transformed into strength as Chinatown communities created the safe spaces of community halls and society buildings. Yet this phrase could also apply to the racist attacks targeting Chinese diasporic communities, individuals, and cherished symbols since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, recounted in the sketches of Karen’s Ruinscapes (2020), a wallpaper work in the domestic space. The vandalism on the lions of Montreal’s Chinatown and Chua Quan Am Temple, and Victoria’s Chinese Public School; an attack on an elderly Chinese man at a Vancouver gas station, and more attacks in Sydney, Melbourne, Brooklyn, and London… These are set against historical injustices and segregation, such as D’Arcy Island’s Chinese leper , colony, active from 1891 to 1924; San Francisco Chinatown’s gate, barely standing after the 1906 earthquake and fires; Nanaimo Chinatown destroyed by fire in 1960; and Vancouver’s 1907 anti Asian riots-which yet was followed by a beautiful friendship gate rebuilt on Vancouver’s Pender Street in 1912, expressing “fxiffi Welcome” to all.” – Whose Chinatown? Examining Chinatown Gazes in Art, Archives, and Collections, Griffin Art Projects, 2021, P138